Seven days in the bottom. Land of the hoodoo stone, the Colorado River, and nothing much of human form or function. Down the Bright Angel, quickly leaving those mule-shit stained and well-trampled miles behind, off over the rolling Kaibab Plateau, with a distant notion of exiting up from through the wild boulders of the New Hance canyon. Afternoons in the cool creek beds worn smooth by ages of slow seasonal trickle, idling in the shade while our clothes dry in the sun. Mornings spent climbing the same rocks to greet the warming sun. We could live here, all agreed, at each camp. Nights spent watching the distant cliffs flare up and then fade to reveal a star strewn sky bounded only by the dark lines of the canyon’s distant rims.

The top. We wander the Grand View Point Grocery and Gift like lost children of some never-contacted tribe on an acid trip. Our eyes flicker madly from brightly colored object to shiny doodad. We stand frozen at the doors of the refrigerated cases. We occasionally stop in the middle of the aisle to gape at the florescent lights while the midwestern tourists stare at us. (But there is music coming out of the ceiling here). They found us in the eddies between the oversized tshirt racks and led each of us out by the hand to the bus bound for Phoenix. I don’t think anyone managed to buy so much as a candy bar.

On the bus ride across the steaming asphalt slapped over the rolling desert plain most of us are still a little out of sorts. Except Josh, who only yesterday was cheerily leading us all through an endless afternoon of waterless canyon. At the moment I’m in no great shape myself, but across the aisle of the bus Josh is dying. His heart is still down in the canyon and he is staring out the window toward it with mournful eyes and a pulse that is getting fainter by the mile. Due to some vagary of time and bus schedules we hadn’t gotten a chance to say a proper goodbye to the canyon, and it seemed that this sin of omission might be mortal.

By evening we are talking with gusto over food (and water, with ice) of the trials civilization had in store for us. Josh, however, remained in critical condition through the evening and the whole trip home. Only momentum carried him back to his life in the city, where his heart returned to him a few days later.

Climbing out of the canyon seven years ago began my fascination with the question “Why do we return?” to the human-built, the technology saturated (and pollution and strip-mall ridden) thing we call civilization. We are seeking something in the wilds that cannot be found in our cities and towns — much has been thought and said about this among the semi-feral. But why do we return? I began to hunt for answers in books and conversations. I watched the process of return more closely in myself and in friends. I left behind my own heart a few times. (I couldn’t tell you where — you’ll have to go and find it for yourself). I began to see the patterns.

At first the answers I found focused on some restriction of the wilds:We are out of food. –Ed Abbey

Mother nature’s quite a lady but you’re the one I need. –Johnny Cash

Wilderness … where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. –US Congress

and while these answers are pragmatic and poetic, they are responding to extreme cases. Abbey couldn’t get more food in his sheer-walled river canyon, but certainly there are wild places where humans can obtain food (say by hiking to the store in the nearest town). Cash’s crooning brings to mind the cowboy era, but today there are plenty of examples of companionship in the wild. My wife is my partner on most rambles. Josh’s sweetie was with us on the Grand Canyon trip. Ray and Jenny Jardine have been adventuring together for decades. Wilderness has a fixed definition for the US government but there are plenty of semi-wild, non-public lands that are not included However, note that stays on National Forest land are limited to 60 days in one place. This regulation has been used to evict (among others) Russian homesteaders in Alaska trying to stake their claim in 2003.

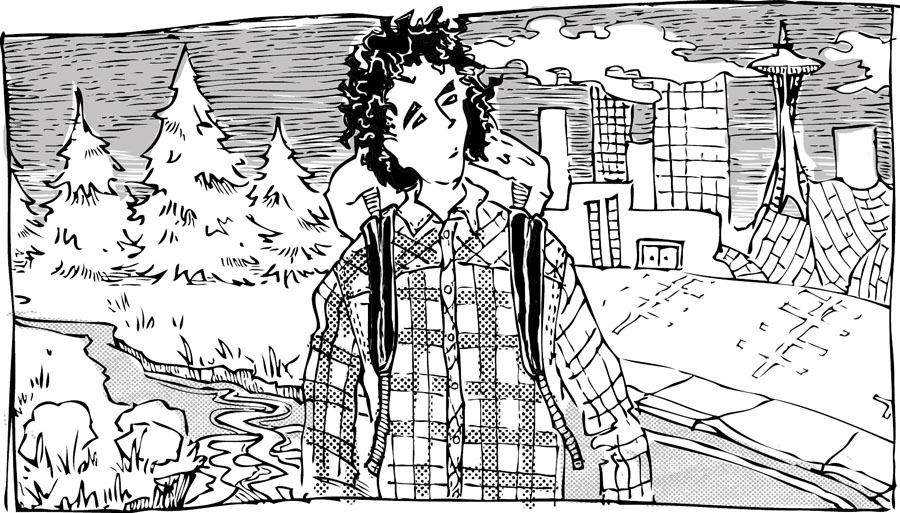

After more serious thinking I realized that we return because civilization pulls us back, not because the wilds push us out. We are drawn to the bits of human beauty in the city, the beacons of the future, even though they are nested amid human-wrought destruction. The wilds have merely sharpened our artist’s eye, refreshed our hope, topped off our soul’s ability to believe in a place where we can live in close proximity and in a future of well made and useful inventions.

On the great mountain (or desert plain or deep forest) we experience a place so untouched by people and majestically indifferent to mankind that by sheer contrast it brings us into focus. The wilds wipe clean the canvas of our imagination (sponging away an overflowing gray-tinted mess of roaring traffic, the old man with hat-in-hand on the corner, the war on tv, and other powerful images of worldsickness), and give us the ability to start dreaming a new masterpiece. We are ready to find a better use for asphalt, to re-channel the the flows of power, to remix our mythology. We return because we belong in both worlds: the wild and the future we are building.