the veins protrude on the top of them

they are tanned

Please bring another turtle to us.

You are a kind man

And when you write nice things

on my paper

My heart aches. My eyes

form tears

I splash to the ground

Wayne Robbins

—AC Church

Ed. Note

Once upon a time, AC Church had an English class at a small-town North Carolina community college. Wayne Robbins was the teacher. I love to hear the stories about this man, his classroom, and the handwritten comments he returned on every assignment. And how Wayne Robbins had turtle medicine. He would rescue them from the road and bring them to class.

AC Church is one of my most important and badass teachers as a poet, writer, and person. In a yoga practice, whenever I hear the teachers thank their lineage of teachers, I always think of how my lineage reaches back to Wayne Robbins. I wonder about who his teachers were. When we decided to include this poem, AC got in touch with Wayne Robbins to ask him for permission to use his wonderful name. He said it was ok, but then we had to email him again for more permission to include his email! You’ll see why. This is what he wrote:

From: Wayne Robbins

Subject: hiya Wayne it's Amber

To: AC Church

Dear Amber,

Thanks for sharing these words with me—It really means a lot.

I tried to be as objective as I can about a poem that has my name as its title. I tried to pretend it was someone else's name, like Jeremy Smith or Esmeralda Sanchez (I made those names up).

That helped. I like the minimalistic approach—no words are wasted and every line creates a clear and interesting image in the mind. And I like how it captures the importance of a mentor's impression on a student. And of course I like how the poem itself has somehow made me write nice things about your paper again many years later. That's pretty magical—

I had forgotten about bringing that turtle to class. I love turtles.

Thanks again for contacting me— Let's keep in touch!

Wayne

Ed. Note, cont’d:

The latest-but-surely-not-last installment in the story of Wayne Robbins: When I left the front porches of North Carolina to be a student of poetry in Los Angeles, California, AC Church made me a pair of mixtapes for my drive across the country. Somewhere before the Tennessee line, I heard Rowboat of Stone. Wayne Robbins & the Hellsayers make sweet music, which you can find in the usual locations, and Wayne Robbins is still a songwriter and poet who teaches in the Carolinas.

—Rachel McLeod Kaminer, Guest Editor

You could call this college a community. If community meant that we were all infants together, desperately seeking a mother’s breast to suck. It was the cheapest formula we could find.

It was a natural fit for me and my siblings: we were home schooled from the start. We had sucked the life out of our mother through a cord, listening to her reading and swimming in her amniotic fluid. We had sucked at her breast while she dreamed up The Greatest Home Education Anyone Has Ever Had, sucked up all she had to teach about proper handwriting and manners and the Great Depression. We sucked our thumbs visiting all the major Civil War battlefields east of the Mississippi and south of the Mason-Dixon. Our father didn’t believe that Martin Luther King Jr. was anybody particularly virtuous, so we sucked that idea right up, too. I thought the Confederate flag was kind of pretty, and I didn’t understand why everyone seemed so pissed about it. Now that mother’s milk had run out – she claimed her knowledge ended at logarithms – we enrolled part-time at the college.

You could call it a community. If community meant that we were all peering into the mirror in the girls’ bathroom, studying the progression of images, searching for a revelation about whether our dreams were going to live or die. The dim light of the girls’ bathroom cast our faces in a fluorescent suicidal glow. I began to wear makeup to cover up the facial discoloration. I got several offers of retribution. Is someone beating you up? I’ll take him. Just tell me who. The truth was that I didn’t sleep and I was getting grey-eyed from my goggles. Grey-eyed goddess my ass. Athena never swam three miles before first period.

If previously I lived in a spiritual realm, sustaining myself largely on books from the library and the living water they always were talking about at church, I now lurched into a grotesque physical one. Cigarette smoke wreathed my face and my body fatigued itself wandering around, picking my way around the browning deposits of chewing tobacco. I found little corners of the campus where students were forbidden to smoke, where I could hide and eat the calories of an athlete. It was the boys’ game at lunch, to see what I had brought to eat. The old men studying there only said hello, only shook my hand warmly, only helped me with my physics equations. The young ones saw me differently and I hated it. My mother lamented my boyishness. Why don’t you wear a nice top? She wasn’t the one walking through the halls to the math and science classes, filled with boys and their wet dreams about being engineers and buying big trucks. I gladly fled my house for early morning practice. No one in that pool was awake enough to question my femininity.

No one questioned much at the college. We were all a bunch of babies and we knew it. Looking for mother’s milk, looking for a formula.

I found mine one day when I looked up to the board and saw a school of fishy equations swimming across the board with sound effects. Swoop wheep hooo, sang the teacher. Chika chicka chickee, that’s our asymptote right there. I stared. This wasn’t math.

Our teacher didn’t have a last name, so we made up rumors. We told anyone who would listen that she had gotten married so many times that she had finally settled on no last name at all. So her name was just Val. Everything about her was pleasantly distracting. She looked like Lady Liberty, slender and graceful with a fat dry erase marker held high in her hand. She had the spirit of the Lady, too. I couldn’t understand a word she said but I wrote them all down. She was going to lift us out of stupidity, she was going to kill mediocrity dead. We were tired, pimpled masses yearning to be free, and she was going to teach us calculus.

I’ve never had the courage to go back to the small wine-making town where I spent my most lonely, peculiar and rewarding year as a Rotary Youth Exchange student 14 years ago.

It’s not because I don’t have fond memories of Alzey; I do, especially of the big-hearted and patient host families who put up with my idiocy as I bumbled my way through the year. It’s more to do with how I remember myself at that time. I was a gigantic loser, and memory has only sharpened this fact. The tender age of seventeen is cruel enough in a country where you actually speak the language and understand the culture. It just gets worse elsewhere.

I haven’t forgotten the days when I wandered around the freezing village alone, killing time until I could go home because I was useless at school. I had, in total, twelve friends – eight were other exchange students who lived in different cities and the remaining were host-siblings who had no choice but to be friends with me. I skipped class like a fiend because I couldn’t understand anything anyways. To top it off, I got fat because I visited the bakery an average of two times a day, stuffing my face with brezeln (pretzels) and käse laugen (cheese buns). Most of this ended up on my face, sadly, giving a look that was akin to Jabba the Hutt.

I was basically a toddler: clueless, slightly mute, with my host family leading me around from place to place without having any idea about what was going on. I reached new heights in the art forms of loneliness and ostracization, covered up with the veneer of pride and stubbornness.

I remember early on, my first host mother, Ute, asking me why I couldn’t be more like their last exchange student, Michelle.

“Michelle was so passionate!” she said, maneuvering the grey minivan in traffic on route to school at some insane speed. “She would always try so hard. Her German was much better than yours.”

I grew to hate Michelle – how outgoing she must have been, how she mastered German in mere months whereas I slogged along, sounding like a 3-year-old with a terrible memory and a speech impediment. Everything came easily for Michelle whereas I made every cultural misstep, screw-up and failure in the book.

And yet, so predictably, as it has happened with thousands of exchange students before, and will happen thousands of times again, there was a light at the end of the tunnel. Many months in, something clicked in my brain. Something changed.

I started writing my diary in German, adding in the English words or phrases I didn’t know, such as the gut-cringing phrase, “oh my god, can you say electric eye contact” in response to a boy I had a crush on. I started dreaming in German. And yes, while I might have only still had twelve friends, we grew close and continue to be to this day. I still was carrying an extra 20 pounds but sometimes, for just a while, it’s really fun to eat everything you want. And then go back for seconds. And thirds. I moved to another host family, one who accepted me for who I was, loser-like behavior and all, and I still get a bit weepy when I think of how they rescued me, and with that, my year.

School got better, too. I switched classes and grades: I attended English with the grade 13 class, History with the grade 10 class and German with the grade 5 class across the street, still somewhat advanced for me. How they laughed at me in the beginning. How I laughed with them later.

I stopped sulking and started enjoying life again.

As I left Germany a year later, sobbing and wearing a ridiculous Rotary Club navy blazer covered in thousands of pins, the customs officer asked me why I was so sad.

“You lived in Alzey? That’s not that great a place,” he said, smiling.

I had no words. I couldn’t tell him about how I had gone from feeling like the most awful person on the face of the planet to feeling like I belonged somewhere. I couldn’t put into words just how much I didn’t want to go home. The transformation from feeling so horribly sad to feeling so incredibly content - all in the space of twelve months - is one that is difficult to explain to anyone, let alone a customs agent.

Reflecting back on it, it was by far the best year of my life. It was also the worst year of my life. And yes, as far as the clichés go, it changed my life for the better.

I’ve gone back to Germany dozens of times since my exchange - my best friend now lives there and it’s a frequent stopover hub en route to somewhere. Yet, every single time, I always think to myself, “Should I go back to Alzey? Should I go back to remember how I felt back then?”

And somehow, just somehow, I talk myself out of it.

Charles had been visiting the Scott County Jail every Saturday for two years. He taught a variety of courses to the inmates, from elementary science to creative writing and U.S. history. For the last fifteen years he had spent five days a week teaching world history to unruly seventh and eighth graders, and he sometimes wondered why he chose to spend his Saturdays at the jail. He wondered when no one showed up, when someone cursed at him, and when the one inmate charged at him (following Charles’s suggestion that the inmate work on his handwriting instead of playing so much handball).

The jail classroom was a mostly peaceful place, but since the incident, the warden had paired each inmate with a guard, making for a new dynamic in the small room. Suddenly there were a dozen men in the cramped space, the guards shuffling in the narrow periphery between wall and table, unsure of how to occupy themselves. They politely declined Charles’s invitation to participate, instead leaning against the walls with their arms crossed, listening to class lectures and discussions, becoming more relaxed each week.

Of all the courses offered, Charles especially enjoyed teaching creative writing but had noticed the absence of one inmate who attended every other class. One Saturday after a lesson focusing on the Civil War he asked Lyle--a polite, attentive young man--if he’d have any interest in speed reading. Lyle looked surprised, but said that he’d come if Charles taught the class.

The next Saturday Lyle walked into the narrow room and sat across from Charles at the long metal table. Charles had noticed the young man when Lyle had first arrived at the jail seven or eight months before, had studied the relaxed posture of his strong, slender frame. He looked like someone who would probably always be a great athlete, despite thinning so much during his sentence. His long greasy hair made Charles think that he would have looked like a Jesus-wannabe hippie if it weren’t for the orange jumpsuit. But it was Lyle’s calm expression that struck Charles the most—he looked kind and gentle, and there was an openness in his eyes, one that Charles felt he didn’t often see, in or outside of the jail.

A group of four guards soon followed, walking into the room talking. They didn’t notice the unusual silence, Lyle and Charles watching them. They were all abuzz of some excitement, and suddenly stopped all together. One of the guards nodded at Lyle and then said to Charles, “Small group. You alright today?”

“Yes, I think so. Thanks.” And the guards resumed their conversation as they moved out of the room, leaving the metal door open behind them.

While the guards had been talking, Lyle had set two books on the table: Daniel Silva’s Portrait of a Spy and a fat physics text.

“One of those speed reads by itself, you know. The other one—well, I don’t think is meant to be sped through,” Charles said, leaning forward on the table and clasping his hands.

Lyle sat back, relaxed into his chair. “I know. I just wanted to show you what I’ve been reading.”

“Good. Why two such different things?”

Lyle looked down at the books as if considering the distinction, but not too seriously.

“I just enjoy them both,” he shrugged. “I studied art in college, so I like these mysteries that integrate art history, but I’ve also always loved mathematics and physics. I have a brain for both, I guess.”

Charles sat looking at Lyle for a moment. He felt a surprise that he hoped wasn’t apparent on his face. He reached across the table, pushed the fat mystery aside and picked up the physics book. Flipping through it he caught glimpses of equations on most every page, graphs and tables full of numbers and symbols, and black-and-white photos of experiments from the 1950s.

“This place needs to update their library.” He set the book down and pushed it back across the table. “Why are you here Lyle?”

“To learn speed reading. I’m so bored here, so it’s just nice to learn something new. And after you mentioned it, I realized that I don’t always fully pay attention to what I’m reading—my mind wanders, you know? There are so many distractions here—people yelling, sounds echoing everywhere, heavy doors slamming—but it seems like if I’m speed reading my attention will be more focused.”

As the teacher of a subject, this was what Charles wanted to hear. But as a man sitting across the table this was not the question he had asked.

Sitting back again, Charles crossed his arms, strangely aware of how unanimated Lyle’s conversation was. The young man was speaking gently and deliberately, at what struck Charles as the perfect level for the echoey room.

Charles took a breath and dropped his hands to his lap.

“Well, I think speed reading can help with focus, but that’s not what I meant. Why are you in jail? You’re educated, polite, thoughtful. I usually don’t ask that of my students, but I’m really curious about you.”

Lyle smiled, and nodded. “Yeah, I don’t seem crazy, right? Well, I’m not in here. It’s out there where I have problems. In here I can just read and draw.”

“And not deal with the pressures of ‘life beyond the walls’?” Charles asked, smiling and air quoting the phrase.

“Exactly. They keep telling me I’m an alcoholic, but I think it’s just that I don’t like it out there.”

Charles was surprised at the serious tone, and had the thought that he shouldn’t be pushing his luck, but Lyle seemed perfectly comfortable with the conversation. Both men were now leaning back in their chairs, appearing perfectly relaxed as if they were sitting at a streetside café some morning sharing coffee and cigarettes.

“But not enough to kill yourself?”

“Well, no. That’s always an option, but it isn’t a very good one.”

“Neither is being in here.”

“I know,” said Lyle. “But I don’t have to worry about much here. No job, no bills, no people nagging you about your problems. Here you’re just surrounded by other people who couldn’t deal with it either.” Lyle looked around as he said this, as if gazing at the others he spoke of.

“So, it’s better in here?”

“Not better,” said Lyle, “Just easier. Somedays. I’ve been in and out of here four times, same stupid crime, which makes you start to feel pretty dumb. And after a few months I’m always eager to get out and start my life over. So that’s where I am now--over the regret, but stuck in that place between boredom and restlessness.”

“Sounds fair enough,” said Charles. “So why learn speed reading?”

“Why did you learn it?”

The question caught Charles off guard in its simplicity; but even in his flat tone Lyle sounded curious.

“Because I do a lot of reading, and like you I wanted to still absorb as much information as I could while speeding up the process.”

“Exactly,” said Lyle, his voice becoming more excited. “I want to read every book in here during the next four months. That’s what’ll get me through this. I don’t know if it’ll make me any smarter or anything, but it’s a goal to set, and my counselor tells me that will help me ‘beyond the walls’.”

Charles smiled and nodded. He leaned down and took a stack of papers and a slim book from his bag, then placed the materials on the table and looked at Lyle. “So let’s get to it.”

Possibly never

achieving enlightenment...

grateful for the ride.

I hadn’t seen Owl’s mouth since the first week out, when Dave from Bakersfield clumsily rolled a boulder over his foot. Owl howled that time loud enough to shake a rain of pine needles onto our heads. New as we were then, we probably laughed at him a little, and nervously watched our bear-like leader for the warning signs of a charge. Instead his beard closed back around his mouth, we all worked hard until knocking off time, and then Owl plonked his steel toe booted foot in the creek until the swelling went down enough for him to take it off. We soaked nearby, quietly wishing for a beer, for a joint, a mattress, a day off, absorbing our first lesson with the creek’s icy chill.

That first week some of us had been wiry punks like Jenna from Fresno, dark goths like Trevor from San Jose, or slick drifters like Bob from Long Beach. We were all there, with various degrees of voluntary, to learn how to work hard and live through an entire day of sobriety. We had all lived through lesser measures – boarding school for delinquents, living with grandma across the state, day jobs, and strict curfews and home drug test kits – but the six month stint of hard labor in the backcountry was a step up for all of us.

We’re now five months in, and sitting around the campfire reading our bi-weekly mail deliver, we all look like Owl. Beards, dirty overalls, white tshirts now brown with sweat, beat to hell boots, hair wild with campfire smoke and creek water and bandanas, we look like the rough street kids who live in the park in the city, but without the dogs. And we smell worse. Five months in, we’re finally starting to figure life out. We’re building trail ten times faster now. Our crew hasn’t had a fight in weeks. There’s a kinship now. Instead of plotting our individual escapes back to the city and a first big score, we’re enjoying our weekends together hiking up into the high country, moving fast without our tools. We are excited for each other’s letters – we cheer with Jenna over good news about her brother’s new baby, we help Dave get over a breakup letter that was for the best.

Owl’s letter is from the office and it has a picture with it. His beard parts like two bears unclasping from a hug. His mouth appears, but this time no howl. No sound at all. We aren’t laughing – it’s us in the picture, covered in blood, firelight gleaming off the bottle in Bob’s red hand.

A few months ago, an old guy with a huge pack came hiking through around dinner time. We got to chatting with Morton the old Marine and he offered to give us a survival skills lecture in exchange for our beans and cornbread. We were still cynical then, but Owl was excited and it sounded better than listening to his harmonica. That was how we learned to snare a deer and butcher it. We talked about it all that weekend never really believing any of us city kids could do it. Mail delivery came Monday on the mule with Linda the camp cook. I had a new pair of boots my cousin sent (to replace the too cheap, destroyed shells dangling from my feet.) Also, tucked away in the packaging – just as requested – a bottle of Jager and a dozen joints, which somehow made it past scrutiny into my tent. I thought, this weekend we’re going to party. Four of us headed out Saturday morning, half jokingly laid a few snares around the lake we’d hiked to, laid out our sleeping bags and built a fire. There was an argument, but in the end peer pressure won out. We got fucked up. It got dark. And then we heard the deer.

I woke up to realize that

- it’s noon

- I’m now sunburnt

- I’m hungover

- I have a huge knife in my hand and a bottle near my head

- I’m covered in blood and it’s sticky

- my three friends are scattered around also covered in blood

- there is a deer’s glossy dead eye staring at me

I scream and run into the lake. As everyone else wakes up, I try to disguise the bonfire’s burn holes in my sleeping bag with additional dirt, recover my camera from a nearby bush, bury the bottle, vomit and bury that too. Then we bury the deer, silently take vows of silence, and head back.

We cleaned up our act, worked hard. I even took pictures of wildflowers on the weekends. I had put that night far behind me, and sent my film to a different cousin to get developed. It was the summer after Ted Kazinsky was arrested. I mentioned our hair and dirt, right? So when this acne-scarred sixteen year old working the drug store photo developer in Palo Alto sees our group shot from the night of the deer – blood like war paint, bare chests, wild hare, knives, no deer insight – he freaks. Calls the cops, who freak and call the Park service, and so on until the photo shows up here in camp with the letter says that Owl has to walk us out of the woods. We’re fired. We’re disowned.

Leaving wasn’t pretty. The fact that we would be out of the woods soon brought back some of our old selves. Bob from Long Beach got angry, even pulled his knife out. In the end, the remainder of our shocked crew helped us pack up and we started the two day walk back to the nearest dirt road. Owl led us out silently, only stopping once slowly to shake his beard, and then got on with teaching us how to walk back into the world.

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

If you bourgie hipster-yuppies ever wondered where we went when you replaced our abandoned factories and crack houses with brewpubs and loft apartments, then I’ll tell you. We never left the Pearl. Sure, we moved to Parkrose and Cully and Beaverton, but we haunt nightly the establishments that were around before you were here to label them “Pearletariat” and “divey.”

But I didn’t sneak past my parents’ bedroom at midnight to discuss rent control or Free People or how farmer’s markets are just so Portland. What’s done is done. My topic tonight is much older than that or you or even this grand, sopping City of Roses. I’m here to find out the answer to a question audiences have been coming back after intermission for since 1600: How does Macbeth end?

It won’t take long for you to figure this out, so let’s remove the means that makes us strangers; I’m not an “A” student. I don’t care what all those buttons do on my calculator, and I don’t care what the toes of a frog look like. I cheat and lie my way through high school. What’s fair is foul and what’s foul is fair. And yeah I do the Sparknote thing. It got me through The Great Gatsby (he dies at the end), The Awakening (she dies at the end), Of Mice and Men (he dies at the end), and 1984 (didn’t finish the summary, but I’m guessing he dies at the end). But, hell, if Macbeth has survived four centuries of war and censorship and drama geeks botching the lead, I should at least give Ole Willy two more hours of my time. Which wouldn’t be bad if I could keep my eyes open. Coach has us doing two-a-days, and I need caffeine and a cast of societal misfits to keep me awake through the final two acts. So here I am.

Coffee Time’s always the same, loveable circus that has served as my midnight community college study buddies since I first started sneaking out Sophomore year: the maniacal barista who won’t take your lip, your special requests, or your credit card (if your purchase is under $5); the macho comic book artist who calls the suicide hotline every fifteen minutes to ask questions you could easily find the answer to on Wikipedia; the comic book artist’s biggest fan, a gossipy, chubby Asian woman who nightly tries to win affection by clipping up magazines into grotesque collages of farm animals; the mom-jean-wearing dancer at the Vegan strip club who rolls her dying pug around in a baby carriage and feeds it banana bread. The main activity in the shop comes from the group of chess players that have a tournament every night from eight until close. This group includes four men all with daggers in their smiles. Two are slobs who gave up on the job hunt years ago; then there’s a lawyer – the only other black dude in the shop – and the man they call the King. The latter has Tourettes and a mullet, wears the same shirt every day (“All three voices in my head think you’re an idiot”), and scares the shit out of the non-regulars by going on absurd boisterous rants about kitchen appliances and pest control. They call him the King because that’s his last name, but also because he takes home the construction paper chess-champ crown almost every night and wears it in the shop the following day. And, yes, like every other piece of paper in the shop, the crown is covered in farm animal collages.

Before you think I’m making fun of these folks, you should know that I need these night urchins. This group has helped me and my C-minus brain breeze through high school. Their collective knowledge has answered every homework question I’ve ever had. Whenever I get stuck, a few times per night usually, I just yell out, “Who the hell knows geometry?” and someone usually comes and does the problem for me. That’s how I found out the stripper is Hispanic (I passed Spanish II without knowing a word of Spanish) and that the collage artist can label every country in Europe. Plus, if no one knows the answer, then the comic book artist knows a guy on the hotline he’s happy to ask for me. He’s got him on speed dial.

But tonight he’s not going to make that call, and I’m not going to yell out asking for help. I’ve got two and a half hours before this place closes, and I’m gonna finish by then. So, what happens to Macbeth?

Let me catch you up. Basically there are these three crazy witches that tell Macbeth he’s going to be king. So Macbeth tells his wife and they have the king over for dinner. The wife convinces Macbeth to kill the king, so he does and frames the servants and then kills them. This effectively makes him king, but then things start to get weird. He and his wife start seeing ghosts and hallucinating, and I think people start to notice how crazy they are being because Macbeth goes back to the crazy witches for some guidance. They say something about some nobleman called Macduff that I didn’t catch but, yeah, that’s about it.

Alright. Got my coffee. Got my seat. It’s the one in the corner, all the characters in view. Act 4. Here goes.

First Witch

Thrice the brinded cat hath mew'd.

Second Witch

Thrice and once the hedge-pig whined.

Third Witch

Harpier cries 'Tis time, 'tis time.

First Witch

Round about the cauldron go;

In the poison'd entrails throw.

Toad, that under cold stone

Days and nights has thirty-one

Swelter'd venom sleeping got,

Boil thou first i' the charmed pot.

All

Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn, and cauldron bubble.

The sound of shattering of glass and the barista yells a string of profanity. She scampers to the back and returns with a broom and dustpan. The King departs the chess table and saunters over to the counter.

“Everything alright there, little lady?”

She stops and stares at him from her crouched position. “Don’t call me little lady. And, yes,” she fires back.

“Just be careful there.” His paper crown dips lower on his forehead as he crouches over her, arms akimbo.

I keep reading.

Second Witch

Fillet of a fenny snake,

In the cauldron boil and bake;

Eye of newt and toe of frog,

Wool of bat and tongue of dog,

Adder's fork and blind-worm's sting,

Lizard's leg and owlet's wing,

For a charm of powerful trouble,

Like a hell-broth boil and bubble.

All

Double, double toil and trouble;

Fire burn and cauldron bubble.

Another curse escapes the barrista. She’s bleeding, and looks back up at the King. “You’re going to lose tonight, you know? You can’t win every night.”

He hands her some napkins. “What makes you say that?”

She wraps the napkins around her finger, and she looks up at him dead in the eyes as she stands up.

“Why are you so surprised?” she replies, then turns, and disappears in the back.

“Can you believe her?” the King asks the hipster in the booth closest to the accident.

The hipster continues typing for a moment, then looks up. “Believe what?” he asks nonchalantly.

This hipster is really the only regular who has never helped me. He shows up each night wrapped in a keffiyeh he never takes off, orders a tea he never drinks, and works on his laptop without looking up. He didn’t even look up the time the junkie stood next to him, stretching his arms up to the billowy ceiling, grabbing for his stash. Even the King watched, but that hipster just kept typing away, shifting his eyes back and forth across the screen like he was watching a tennis match. I wouldn’t mind, except you know this dude’s a whiz kid and could probably do calculus blindfolded. He’s an amalgamation of every nerd I’ve ever met or seen in a 1980s chick flick. Skinny and pale with thick glasses and bad allergies, his head so full of thoughts he can’t hold it up straight. A part of me feels a little sorry for him. He’s so lost in his thoughts that he doesn’t notice the passion play of crazies surrounding him. You can get wireless at your house. Why does he even come here?

But, again, I’m not here to find the answer to that question. I’m here to figure out what happens to Macbeth.

The next hour is a blur, interrupted only by a couple shouts of “Checkmate!” from the crew of wretched souls winnowing their way to the exciting conclusion. While this is going on around me, Macbeth does some seriously screwed up stuff. He orders a bunch of people to be killed, including Macduff’s family. I think they escape, but I’m too tired to reread that section. I need to refuel.

Two a.m. is the witching hour at Coffee Time, and each night it is marked by the cheers of the chess players. Tonight the lawyer has defeated slob number two to take on the King in the final match, which begins promptly at 2:30. The barista kicks us out at eight minutes ‘til three (the clocks at Coffee Time run eight minutes fast in the evening and twenty-three minutes slow in the mornings), so everyone gets up for their last cup of the night. And since we’re all sleep deprived and overcaffeinated to begin with, things really start to get strange. Only the regulars are left at this point, and, with the exception of the hipster, we’re all waiting in line for our next cup. The barrista is yelling at the machines. The collage artist chitchats nervously with her love about tonight’s masterpiece, a rooster for her niece. She’s rubbing the glue from her hands furiously. All the while, the comic artist ignores her and gazes at the stripper, who’s feeding her pug small bits of banana bread and chatting to it as though it were a baby.

I’m just as jittery as the rest. I got a double shot in this one, and I want to yell. I want attention. I want to know what happens to Macbeth.

Doctor

I have two nights watched with you, but can perceive

no truth in your report. When was it she last walked?

Gentlewoman

Since his majesty went into the field, I have seen

her rise from her bed, throw her night-gown upon

her, unlock her closet, take forth paper, fold it,

write upon't, read it, afterwards seal it, and again

return to bed; yet all this while in a most fast sleep.

Doctor

A great perturbation in nature, to receive at once

the benefit of sleep, and do the effects of

watching! In this slumbery agitation, besides her

walking and other actual performances, what, at any

time, have you heard her say?

In line, the lawyer interrupts the collage artist, “I’m throwing my towel in early tonight. Who wants my spot? How about you?” She’s still rubbing her hands.

“I’m afraid the pieces will stick to my fingers.” She laughs and looks at her hands. “Out damned glue! Who would have thought one jar would have so much glue!” She laughs again and looks over at the comic artist, now on the phone, asking the hotline volunteer where Dunsinane Hill is. The lawyer passes him.

Doctor

This disease is beyond my practise: yet I have known

those which have walked in their sleep who have died

holily in their beds.

The lawyer asks the stripper next. “You want in?”

“I’m afraid Mr. Duncan wouldn’t have me leave his side, would you, Mr. Duncan? Would you?” She kneels down and lets the pug lick her face.

Doctor

Foul whisperings are abroad: unnatural deeds

Do breed unnatural troubles: infected minds

To their deaf pillows will discharge their secrets:

More needs she the divine than the physician.

God, God forgive us all! Look after her;

Remove from her the means of all annoyance,

And still keep eyes upon her. So, good night:

My mind she has mated, and amazed my sight.

I think, but dare not speak.

The lawyer approaches me, “You want in?”

“I’m trying to find out what happens to Macbeth,” I reply, half hoping he’ll give me the answer.

“Is that the one with the black man falling for the white chick?”

“I don’t think so – At least, I don’t think he’s black.”

“I don’t remember what happened in that one anyway. He probably died in the end. They always do.”

Doctor

Not so sick, my lord,

As she is troubled with thick coming fancies,

That keep her from her rest.

His last stop is the hipster.

“You want in?”

“In?” the hipster replies, not looking up.

“Do you want to play chess? I’ve gotta take off early tonight.” The hipster shifts his eyes to the chess table. Everyone in the line is staring at him, anticipating a polite rejection from the milquetoast.

“Yes.”

Doctor

Therein the patient

Must minister to himself.

“Are you headed to bed?” the King asks.

“Directly,” replies the lawyer. “I’m sure this young man will fight you bravely.” The lawyer grabs his trench coat and exits.

The hipster closes his laptop and walks to the chair opposite the King. He sits, the King stares. They start.

I look down at the pages. “What happens to Macbeth?” I whisper.

Macbeth

I have almost forgot the taste of fears;

The time has been, my senses would have cool'd

To hear a night-shriek; and my fell of hair

Would at a dismal treatise rouse and stir

As life were in't: I have supp'd full with horrors;

Direness, familiar to my slaughterous thoughts

Cannot once start me.

A yell from the slobs erupts.

“What happened?” the barrista yells from across the room.

“She’s dead. The noob killed the King’s Queen,” says the slob.

She cackles. “See? What I tell you?”

The collage artist gets up to watch. The comic artist follows. I look to the stripper.

“What happens to Macbeth?” I ask her. She shrugs and turns to her pet.

“I’ll ask Mr. Duncan. Do you know what happens to Macbeth, Mr. Duncan?”

No answer.

Macbeth

She should have died hereafter;

There would have been a time for such a word.

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

I glance at my watch. It’s 2:39, and I have thirteen minutes. My legs are shaking, my hands are sweating. The hipster moves his rook. The collage artist rubs her hands. The barista chats with the cappuccino machine that she’s cleaning. The stripper and her pug join the chess audience. The King watches his bishop fall.

“What happens to Macbeth?” I ask the barista.

She keeps grabbing at something on the counter, as if trying to crush a fly. “It was right in front of me a second ago.”

“What was?”

“My knife – What was your question?”

I give her a puzzled look. Then repeat my question.

“He makes Tamara eat her children. Hell if I care.”

Macbeth

They have tied me to a stake; I cannot fly,

But, bear-like, I must fight the course. What's he

That was not born of woman? Such a one

Am I to fear, or none.

The stripper holds her hands to her mouth. Her gasp escapes with the rest. The King places his opponent’s queen off the battlefield. What’s done cannot be undone. It’s 2:47.

“You’ve got five minutes to get the hell out!” screams the barista.

The crowd doesn’t move. I use this as another opportunity to ask.

“Hey could any of you tell me what happens to Macbeth?” I’m met with silence.

The collage artist rubs her hands slowly. The comic squeezes his phone. The King stares at his king. The hipster stares at his rook. The only sound is the barista groping around for her knife.

Macbeth

I will not yield,

To kiss the ground before young Malcolm's feet,

And to be baited with the rabble's curse.

The hipster places his fingers on the rook.

The stripper stops petting the pug. The collage artist ceases rubbing her hands. The comic drops his phone. The barista holds the knife up, gazing at her reflection in the shiny dagger. She looks to the clock. She opens her mouth, but I stand up on the table before she can say anything. I scream; I scream as loud as I can, “What happens to Macbeth? WHAT HAPPENS TO MACBETH!”

My face is flushed. A drop of sweat falls from my feverish forehead. The room is still.

The hipster moves his rook. He looks at me. The audience follows his gaze to me. He says, “Macbeth dies at the end. Macduff kills him.” He then turns to the King. “Checkmate.”

The audience erupts in a violent boom.

The night ends like all others. The barista yells at us until we’re all out, with the collage artist being the last one collecting her scraps. I stuff my book in my back pocket and walk out as the barista places the knife in the drawer.

Macbeth dies at the end, but so do we in our own way. The difference between us and Macbeth is that we don’t care about good and evil in Coffee Time. Heroin won’t even get the hipster to look up from his computer, and we laugh at the prank calls to the suicide hotline. We’re just a bunch of soulless silhouettes of our daytime selves in there, amoral shells of humans driven by our needs for caffeine and attention and table space. We walk in, play our role, and walk out; no one hears from each other until we surface for the next midnight session.

The King once told me that everything in life happens twice, first as tragedy then as farce. I see the tragedy in life – the addiction, the poverty, the illness. But I see the farce, too – the dumbest of farces – told by whoever is dumb enough to tell it, whether that may be me or Mr. Duncan or the green copper Portlandia herself, clutching her trident while stooping down to scoop us up so we too can see the farce, to save us from the tragedy, the sound, the fury, the insignificance, the grey and rain.

Across the street, I turn around and stare back at Coffee Time as though I’m Macbeth looking Macduff in the eye, ready to whisper the final words. The barista closes the curtains, turns off the lights, shuts the door, and turns the key.

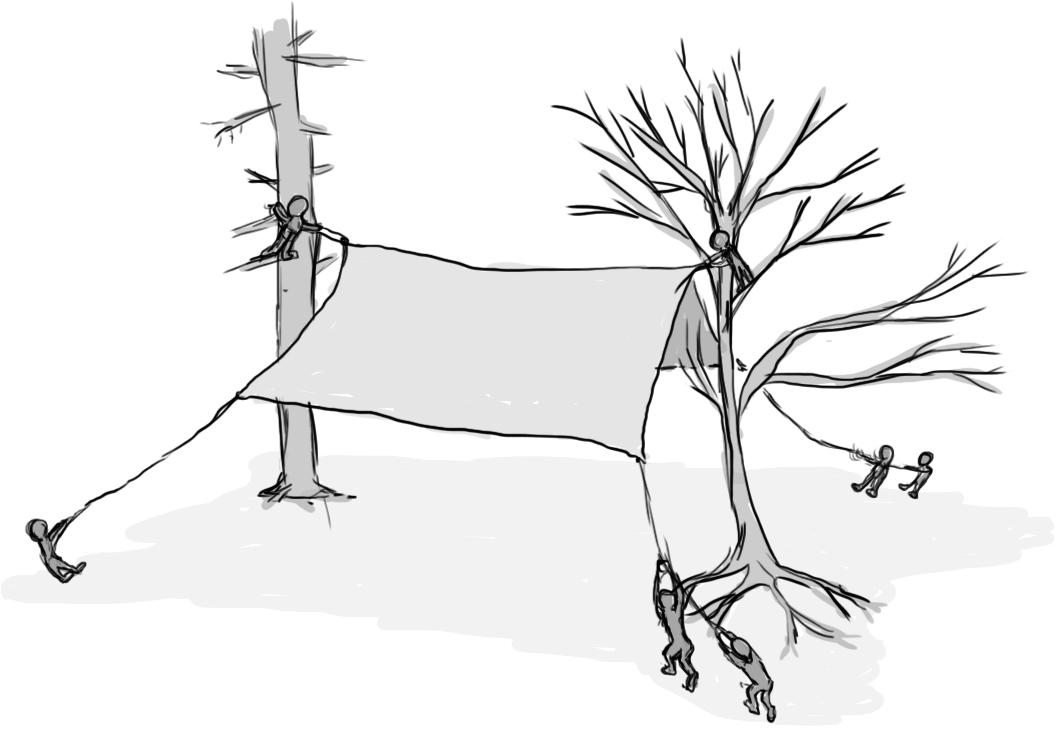

Each year a temporary village of 15,000 people springs up out of the forest over a few weeks time. Saplings and deadfall are cut to form long counters, kitchens, serving tables. Clay patted by many hands into hearths, around metal drums to form ovens. Slender men and women scamper up trees, towing ropes to the highest branches, stretching taut tarps that shelter a hundred from summer rainstorms. Wood is gathered.

The kitchens go in first, in choice locations, some near meadows, downhill from water. Gravity, and donated dollars, run the water filters. Camps grow around the kitchens. A place to fire sit, play music, and sing. Where you quietly wander in the morning, holding your bowl, filling it first with smoky black coffee, then oatmeal. Sitting around the remains of last night’s fire, feeding it for the new day.

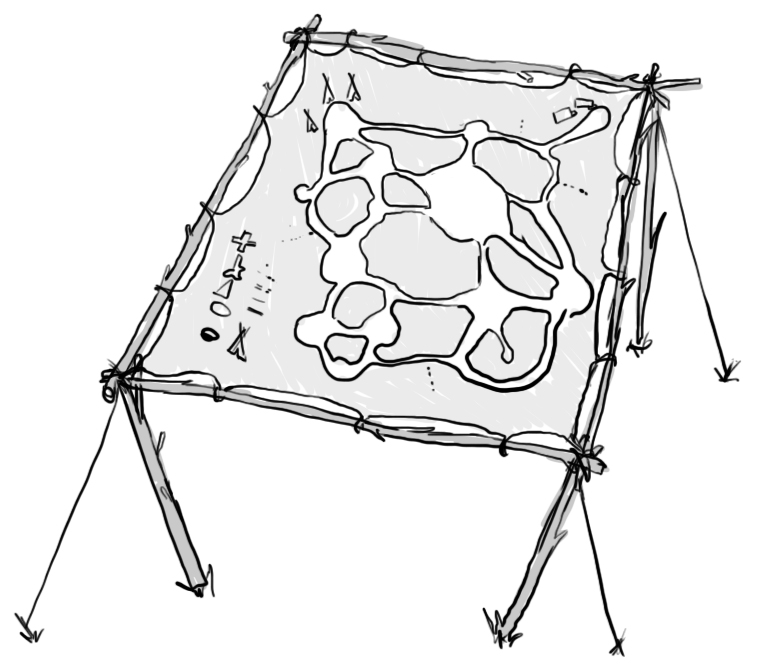

You wander from your home kitchen to another, your feet adding to the thousands of footsteps forming the network of paths between them. The hand-painted map at Central Supply, near the rap sheets and message boards, shows the network you’re forming. Different each year, for each forest, each state. Feet on the land, Rainbow People gathering.

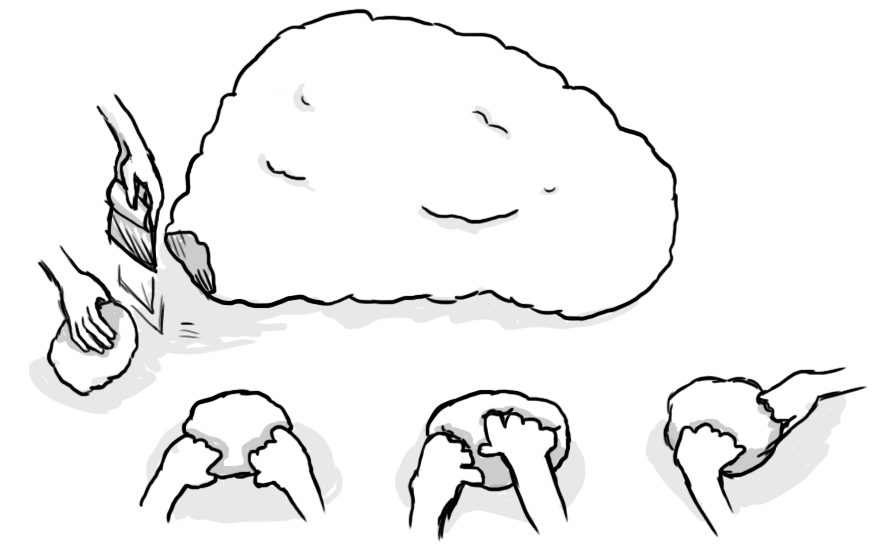

The way to Lovin’ Ovens is easy to find by smell. Dough in the forest. Rolls for thousands at dinner circle need kneading all day. You’ll help for a few hours this morning, circled up to the 8’ x 12’ plywood trestle table, covered first in plastic, then a dusting of flour. Three people grunt as they up-end a 100 gallon tupperware of first rise dough.

Dough-cutter-wielding bakers divvy out five pound sections to each bleach-water-clean pair of waiting hands. Knead like this: fold in half like a lover, turn a quarter turn, repeat until your thumbprint bounces back just right.

The afternoon is spent exploring: a cup of chai and a quiet heart-to-heart with a stranger, sitting on cushions under tapestries hanging in the pines.

The discovery of Hammock Village, where a beautiful woman rocks in a third story hammock, playing the accordion with her toes and singing with her eyes closed.

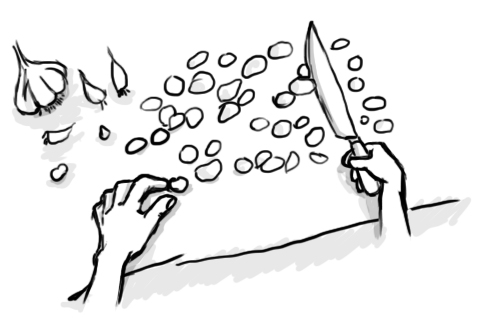

Instant Soup is cooking up their tenth cauldron of the day, and you help peel and chop a mound of garlic as big as a baby, destined for a pot you could bathe children in. Just as you finish, forty pounds of potatoes arrive from Central Supply in a wheelbarrow with mountain bike tires.

Resting in a patch of sun, smelling the garlic on your hands, you watch the nudist parade pass by on the main trail, banging pots and pans, picking up in numbers. That the hairy man in the back has a tag of TP stuck to his butt does not deter people from stripping down and joining.

You’ve heard that the kettle corn kitchen is making chile-brown-sugar next, and that starting at dark thirty, Lovin’ Ovens is making pizzas ‘til sunrise. And a kitchen to the south that sprung up yesterday has spread word that they’ll be making pancakes through the night. It’s somewhere down the trail past the place you had a cup of coffee strained through a dirty t-shirt while pole dancers performed on stripped trees.

You will find it, unlike the wandering saxophone player who haunts the woods. You’ve been looking but you haven’t found him yet on the network of trails.

And you still haven’t gotten the courage to cross the creek via the catapult bridge, preferring instead the log bridges near the circus tent Granola Funk, where talent shows and bluegrass happen nightly. It’s a bit of a walk, but you also get to pass by the Shanti Sena medic outpost, C.A.L.M. and the Barter Circle.

There, a novice tarot reader who gives you a reading in trade for the eagle feather in your hair, offers an excuse to open up. In Tipi Village a man tells stories from a richly illustrated book. Uphill, on the outskirts of the gathering, Bus Village is filled with vehicles right out of Lloyd Kahn’s Tiny Homes – caravans and painted school buses and home welded, half-this-half-that homes.

Walking in a forest path, headlamp off so as not to blind those who cannot afford headlamps, you find your way along the now familiar trails, feeling for roots with your feet and the moonlight. An owl hoots, and then the shadowy stumps begin wildy dancing, erupting with beatboxing and strobe headlamps. A dance ambush!