Sing, oh muse, of that night at Lonnie’s

(spared from the flood by the hand of God)

filled with Vandy girls, spray-tanned till tawny.

To the Stage, then Tootsie’s, and Robert’s just to catch my breath.

I saw Ophelia, whose temperance met an early death,

and parsimonious, underneath an awning

I gave her cigarettes, for alms, or calming.

The cops had cordoned lower Broad

and in an alley, within a block of Hooters

we were accused of being looters.

I ended up alone at Coco, later on,

with Graham Parsons on the tired speakers,

eating poutine with uneven hands

among my fellow drunks and the listless tweakers,

slouching and squinting at the dawn.

The rumor coming from the newsstand

was ‘Piranhas loose in Opryland.’

I placed another order: macchiato, jam, and toast,

and thought myself among the ranks and files of the dead.

Headlights in the half-light looked like the eyes of ghosts.

I called a cab, bussed my plate and trash

and remembering that I was short on cash,

opted to hoof it back to East Nashville instead.

When I reached the bridge, I turned my gaze

to the river, sated, underneath me.

I think that if it were the Lethe

I would tiptoe into the swell,

eating sugar cubes and asphodels.

I should have joined the volunteers these last few days,

and the shame was like venom, coursing through my chest.

(like a Pentecostal on a vision quest.)

I passed the Quonset huts and the Tyvek domes,

took a mental inventory, to see what I could spare.

I have a kitchen full of beer and kitsch,

a hallway lined with Hatch Show prints,

books on poker, Descartes, and car repair.

The walk felt long and when I got home

I bagged some sweatpants and a garden gnome.

The gesture being useless; I’m aware.We have a rare disease. We call it Satisfaction. Most of us contracted it in our early twenties, although it germinated in many even earlier. At the time of publication, much uncertainty exists as to our ability to live in close proximity to normal society on a permanent basis. Our disease is widely believed to be contagious and the consequence of God’s great displeasure besides.

Among the infected too there is debate on the merits of various colony configurations, but it is now clear to us that we must live together. As for being contagious (probably, hopefully) and displeasing God (certainly we provoke wrath in the upholders of modern society’s main tenets) these factor into our decision also, but our calculation is different. Our main goal is to infect. Don’t be shocked. Let me give a full account of the disease, its symptoms, diagnosis, and prognosis and you can judge for yourself.

Satisfaction has its roots in modern American comforts. For the majority basic food and shelter were a given, electricity and gasoline did our heavy lifting and entertained too, a large number of our generation attended college, we moved about the world at will. With these comforts came modern excess — fierce competition amongst a population uneasy with the idea that there is no longer a frontier, the quiet isolation of suburbs cars television and fear, ubiquitous pollution, rampant obesity, common callous exploitation.

Against this backdrop we set out with the natural goal of every generation, to have a better go of it than our parents did. The only difference for our generation is the ambiguity of what exactly better means. To attain a standard of living with more material comforts than our parent’s generation we would need to make vast sums of money. It sometimes seems that it would be better to have fewer modern ills — but this line of reasoning is contentious.

These excesses are alternately blamed on random chance and touted as absolutely, scientifically (unfortunately) essential to our standard of living. The suggestion that comfort might be weighed on a more rational scale against excess is quickly shouted down. So our generation set sail under the flag flown by the generations before us, but was troubled by the shadow it cast.

Often the first sign of a change in course, the first sign of infection, is a sudden outburst of “Fuck it. I’m happy here.” This thought jumped out at me many times. The backdrop could have been one of several places in the South — the rhododendron over the rolling mountaintops, the sandstone bluffs, the rocky creeks they stood high above, or just a patch of sunny grass — but the friends were always dear ones and the setting was always beautiful. The thing you are dismissively cursing is harder to pin down, but in your mind the comfort side of the scale is beginning to wobble off the ground. If these impulses go untreated, the progression of the disease becomes sure and swift. Something deep inside of you shifts and resettles. The scale now balances freely.

Aldo Leopold experienced this shift watching the pale green fire die (and realizing the wolf he just killed had an inner life which deserved existence), Thoreau by idling while his beans grew beside Walden Pond (and growing his own inner life like corn in the night), and Abbey by (… well cagey old Ed never told anyone but probably…) seeing his first buzzard soar over the desert (where he is today, either under the sand or reincarnate in the buzzard).

The exact catalyst varies but the disease is now entrenched. Friends, time, beauty, love, simplicity, silence all take unquestioned precedence over riches, society’s expectations, modern wants. You take desires, distill down your needs, and skim off your wants. You lose your possessive sense of places and they take up possession of you. You are satisfied.Our generation is now approaching full adulthood. Many of them have garnered real jobs in engineering, business, management, finance. They are poised to make the vast sums of money they will require and are making names for themselves. We, the infected, took seasonal outdoors work, internships, artist-in-residencies, traveling, jobs at tiny non-profits, more education.

We too are making a name for ourselves, although it is too often mispronounced. Our parents have diagnosed a bad economy, wanderlust, a return of the sixties flower children, even sloth. Pundits group us in with the larger mass of ‘twenty-somethings’ or label us ‘green’. Satisfaction is often misdiagnosed. (Fair enough. If it was a medicine rather than a disease the bottle might read: “Warning: side effects may include making art, bicycling, knowledge of eastern religious practice, waking up in the woods… ” and so on for at least a page.)

Satisfaction doesn’t mean spending our lives meditating in full lotus on a mountaintop, on our parent’s couch, or shopping at trendy organic supermarkets. The hippies of the sixties were “a generation searching for the bars of the cage.” Forewarned, we are ready with hacksaws. Lumping us with the bulk of our job hunting generation isn’t correct either. Seeking a (high paying) job or a (long disappeared) secure career is different than seeking a (satisfying) vocation. While the New York Times worries that “social institutions are missing out on young people contributing to productivity and growth,” we would rather contribute to something more worthwhile. Labeling all of our actions, motivations, and thoughts as “green” is perhaps the most common misdiagnosis. Aye, we are people at home in the woods. We’ve read our Muir. We ride bicycles. We can cook a healthy meal from scratch. But our motivation is different than the “green” movement as motivated by advertising-induced guilt to try and protect “our” environment.

Enough about what Satisfaction is not for now. It must be understood for what it is and where it is going, for in it we see the future.With Satisfaction comes the need to act. We must learn to settle the scale on a balance between the good of comforts and the harm of excess, to live healthily with Satisfaction. If humankind ever had this knowledge we don’t now and desperately need it. We spent so long struggling to survive against nature that we didn’t realize we had made it and before our thinking caught up we had plunged ahead trying to conquer nature, to our detriment. So it is our generation’s job to bring humanity’s way of thinking up to modern reality, to put balance to the test, and to teach what works well. Our gauge will be what promotes happiness, fulfillment, direct connections to other people and the natural world, and simple beauty. Our metric will be what works not just for our generation but will work for the future of the natural community around us and for our grandchildren’s generation.

We worry, though, that Satisfaction may be fleeting, that modern society’s attitudes may spread like its strip malls over our souls before we find our way. That without lots of encouragement and inspiration from like-minded people, we will wander lost. So we have decided to band together and form our own society — where everyone can pursue their own vocations, understand their connections to each other and the land, walk to see a friend, gather around a common meal, test these wild ideas. We have no illusions of complete self sufficiency, complete isolation from modern society, or complete ease in our world. We merely hope to bring more value to the world than we take from it, support ourselves well, and so become contagious. Someday we hope to see our children set off on long walks or bicycle journeys to like minded communities scattered across the land, and return with stories and ideas and news of how Satisfaction is spreading.Abbey recommends

poetry and revolution

before breakfast.

get up, sing a song,

write a poem,

watch the sun come up,

slip on your dark clothes,

blacken your face, pick up your tools

and go out to meet the enemy —

yellow ‘dozers standing in a field,

chill, the dew formed on them,

quiet, cold (it’s been hours

since their engines ran),

defenseless.

do your work, slip home,

change softly, shut off the alarm,

make coffee,

oatmeal and raisins,

squeeze some oranges,

have breakfast.

A cold thrust of wind and rain lifted the tent off the ground. I clutched the top with my numbed fingers, finding purchase at the point where the poles crossed in the center. The tent went horizontal in the air, and I braced to keep it from flying into the lake. I wrestled it down when the gust slackened. It had been cold and rainy all day, as I hiked to over 10,000 feet in the wilderness of Ecuador. I managed to fix a broken tent pole that night, crawl into my dry refuge and squeeze some emergency energy gel into my mouth while thawing in my cold-weather sleeping bag.

I’m not crazy. I did not have fun. Yet two more times during my five-week solo trip to Ecuador I returned to the wilderness to revel and roam in mountain landscapes without encountering anyone else for days. Exploring nature wasn’t the central purpose of that trip. It isn’t even the central purpose of this story. What I really want to tell you is how I got there. What made me cut myself off and not look back to safety and comfort when what I wanted to do was out there.

Two years before Ecuador, I disappeared from my family and friends early in the summer. Only a few months out of high school, I showed up to college with only what I was wearing. I waited in line that first day to get my blood drawn, my dimensions measured, and my head shaved. From the first shouted commands of the upperclassmen, I learned how to tune out everything but the information required to stay out of trouble.

I never fit into the military mold. I remained pensive behind the poker face of attention and compliance. Instead of working out or studying, I did just enough to get by. I dedicated myself to personal projects like speed reading, competitive chess, or sneaking away with books that would broaden my perspectives about the military. Although I excelled, I was unhappy that my future purpose was still unknown.

Furthermore, I didn’t connect with the personality typical of the place. I didn’t connect with the military’s escapists either. Escapists have the attitude of tolerating things until the next chance to pretend to be normal; that is, to get out and party. One weekend we were allowed out of the campus gates, but I didn’t have any plans. I still felt the need to get away and I took the opportunity, walking out the gate with a small pack and an extra pair of clothes. We weren’t supposed to roam around town out of uniform, so I used a bathroom in a museum nearby to change. I then slipped under a bridge and along the water’s edge to stash my uniform under some rocks. I enjoyed my weekend: walking for miles, reading Cat’s Cradle and sleeping on the ground. I spent the first night in a park, where I had a surprise awakening when a dog sniffed out my location on his morning walk.

I decided that the military wasn’t the place for me, so I transferred after my sophomore year. Normal college drew me in. I was on board again with a legitimate organization that I had no reservations about. I was doing something valuable and respected by mainstream society. But I was still juggling personal goals. I sped up my goal to learn a second language before graduation. I looked up language schools in different South American countries and organized my own trip. I talked on the phone with the head of a Spanish school in Quito, and booked my flight.

I read up on the country’s politics and history the week before going and made my first friend in the airport, waiting for the flight from Miami. On the flight over, I had to repeat to the incredulous tourist sitting next to me that I was neither sightseeing with a friend nor receiving some kind of institutional support or class credit. I was on my own, pushing myself to learn outside of my comfort zone.

I’ll always come home to recharge, to share ideas with my base of friends, and to build my confidence in more traditionally accepted pursuits. But to really push my boundaries outward I need to take a step back from common experience and venture out into the world with a new vision of what is possible in life. Sometimes waiting for the right opportunity is just too normal to work.There occurred a sneaky move in the development of public transportation infrastructure in the United States around 1940–50, one that set us back considerably. But of course, at the time, those involved truly believed they were looking out for American citizens, doing their part to improve our quality of life, and especially theirs. Could you envision a rail-oriented structure in our larger cities? How about a Los Angeles or Detroit that moves more like San Francisco? It is safe to say there was no single cause in US history that manipulated our system to be so auto-dependent; the reasons are varied and numerous. However, there is one event in particular which could be argued to be the catalyst of the automobile trend while helping erase the possibility of public rail transit as a viable form of transportation.

The Great American Streetcar Scandal was executed with such a swift and dexterous hand that even the US Supreme Court eventually noticed. The list of players is impressive: National City Lines, American City Lines, Pacific City Lines, Standard Oil, Federal Engineering Corp, Phillips Petroleum, General Motors, Firestone Tire, and Rubber and Mack Manufacturing. Their ultimate goal, which they accomplished, was to buy out all of the streetcar companies in major US cities and dismantle the infrastructure, clearing the public transportation slate and laying the foundation for a system reliant almost entirely on combustion engine mobility. It was clear they were in cahoots and were all convicted of criminal conspiracy in 1950. Forty-five cities that all had systems comparable to San Francisco were affected, including: Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, Los Angeles, New York City, Oakland, Philadelphia, Salt Lake City, St. Louis, and Tulsa.

This event precipitated the notorious pattern of development that distinguishes the US from all other developed countries in the world and played a huge part in our resource-consuming lifestyle: sprawling subdivisions, countless miles of impressively engineered freeways, acres of parking lots, and drive-through restaurants; a world molded by the needs of the car. What is important to note is that this occurred so early in our development as a nation (mid 1940s) that we don’t really have a collective memory of an established system existing before the automobile; there is nothing to miss nor any romantic yearning for how things used to be. And the streetcars of San Francisco seem to us a taste of European culture, an exotic novelty that is appreciated, but no doubt out of place in our idea of American culture.

Though this event is, for the most part, lost in our society’s collective memory, there is a classic 1988 movie that cleverly delivers the story: Who Framed Roger Rabbit. For those of you who have seen it, there is no forgetting Judge Doom, the movie’s main antagonist. He plots to destroy Toontown, a cartoon world reminiscent of America’s romanticized “Main Street”, with DIP, a deadly combination of paint thinners. In its place he envisions a freeway, and the parallels between Judge Doom and GM (with Firestone and Standard Oil) are unmistakably clear. Doom says, “… I see a place where people get on and off the freeway. On and off, off and on all day, all night. Soon, where Toontown once stood will be a string of gas stations, inexpensive motels, restaurants that serve rapidly prepared food. Tire salons, automobile dealerships and wonderful billboards reaching as far as the eye can see. My God, it’ll be beautiful!” Eddie, one of the protagonists, is a private investigator hired to find out who killed the owner of Toontown. When he hears of Judge Doom’s plans, he responds, “Nobody’s gonna drive this lousy freeway when they can take the Red Car for a nickel.” The “Red Car” being Los Angeles’ profitable and reliable public rail system before GM gained ownership and dismantled it. By the end of the movie, the good guys prevail, as one would expect in Hollywood; Judge Doom is destroyed, the freeway never gets built, and Toontown and its residents live happily ever after. Unfortunately, in the real world, the bad guys got away with a nominal fee after being convicted of conspiracy and still got to build their freeways.

To all those who make conscious choices to abandon the vehicle when not absolutely necessary, we are unplugging, little by little, from the powerful reign of the auto industry. But the more important message here is that we are plugging back in to the idea of Toontown; of a bustling community where people bump into each other on the street, where strangers share their personal space with the world around them. Instead: carpool, take the bus, take the train, ride your bike, roller skate! When and where possible, remove the barrier that isolates you from your surroundings and be open to meeting a stranger and having a conversation that seems to be just the right exchange at just the right moment.Northern Alabama drips in the summer heat. My parents ride bicycles four miles to the river after dinner. They come upon friends along the path, and fly along in a swooping wasp-like pack. The greenway runs along a drainage creek, wide enough that they ride in side-by-side pairs talking, or peel off and go on ahead, watching for a heron and listening to the wall of insect sound. The summer’s new biking friends seem interesting from the news that trickles across the country through the phone lines. One couple shares with neighbors their margarita machine, an appliance as large and complex as an espresso maker. Another man is seventy-five and has already accomplished his retirement goal of riding 100,000 miles. My parents and their new bike friends have dinners together and take drives to Mississippi and Georgia to ride the rail trails.

To keep cool my dad rides in a wicker mesh garden hat. Here is a man whose daughters once had to coax him away from the television to go on a walk; now he coaxes his wife to ride in the heat of the afternoons, not wanting to wait even for the relative cool of after dinner. One weekend he went with the septuagenarian to Georgia and rode seventy-two miles in one day. Could I believe it? Boy, was he sore after, but it felt… good.

They took their bikes with them to Florida and rode along the open roads, enjoying the beach winds. The cars and RVs that lumbered by did so in accordance with the state park’s speed limit, my mom reported triumphantly. It was really nice.

But then, last week Mom boasted that they’d biked all the way across town to have dinner with my sister, a 28-mile round trip. I found myself imagining the route. Did they really bike on Bob Wallace? My parents, riding their low-to-the-ground recumbents?

Last year a car a hit a cyclist on similar road nearby. A friend sent me the article in which most of the online commenters blamed the victim. “Even children know not to ride their bikes in the street for fear of being hit by a car.” “Save your b.s. about the vehicle operator being at fault. If people want to ride their bikes on busy public streets they’re taking their own chances.” Another commenter noted that “Regardless of the laws, its kinda hard to see a bike in that kinda traffic esp in the dark with the headlights shining in our face.” In Alabama, “the streets are made for CARS AND TRUCKS!” they said, and bike riders deserve whatever they get.

Some people genuinely feel that they should not ever have to move over or slow down to pass a bicycle on the road. I could just imagine the “bro” bearing down on my parents (he would be driving a lifted truck with a muddin’ snorkel). In the cold calculation in his face, there would be a righteous glint in his eye as he got ready to give them a little scare. My dear sweet parents, biking on the road with those heat-crazed maniacs?Wait a minute. My parents are biking. They are exercising, being social, spending time outside, watching less television. Let’s talk about my dad, compare the risks of being hit by a car while biking with what he was doing before. Which life choices are better for his health?

My dad is an engineer, a master of making complex drawings on the computer, a man who can build anything. After driving his 30-minute commute, he crunches his 6’4” frame into an office chair for eight hours, then drives the half hour back home. He proceeds to watch (by his own estimate) an average of four hours of television per night: keeping up with at least twelve shows (plus the Braves) on the gigantic flat screen that dominates the living room. Four hours a day? That’s less than the national average, but still the time equivalent of working a second part-time job. A full time job, an hour commuting, and a second part-time job committed to tv-watching. My dad is a busy man, but he spends a lot of his time passively being entertained. He does not have a lot of time left over for sleep. Or exercise, or time with friends, or time outdoors.

Could biking be a way for my Dad to rediscover what he actually likes doing, reconnect with himself and find some adventure? He and my mom bike for an hour and a half every evening now. Nearly every day, for the past six months. And my dad, my dad, is the direct motivator, encouraging mom to brave the heat and bike down to the river. They started slow and have moved to longer rides, biking forty or fifty miles along trails. My dad’s emails contain a new sense of pride, a surprised happiness that his body can do such things on its own. His knees feel better since he started biking. He’s talking about long bike tours next, overnight tours.They’ve made new friends, and started interacting with nature with an intensity I haven’t seen in them since my childhood camping trips. Where they live is built around the automobile and the television and the air conditioner. There is no mass transit, things are spread out way beyond walking distance, and there are few good gathering places. You see your friends in the aisles of Wal-Mart and catch up briefly, and then retreat to the next refrigerated box. It’s a system that is hard to escape.Yet they’re doing it. They rode in Critical Mass last month. My dad now knows about Warm Showers, and he watched that viral video of Amsterdam and found out that streets and even street lights just for bicycles exist. He’s reading blogs by people who are taking a while to bike across country, and making plans for next summer.There is some measure of peace to be found by biking down to the water, a self-sufficiency in finding your body can go places under its own power. They are making themselves happy, their daughters proud. Still the picture of the grinning good-ole-boy bearing down on the two little recumbents on the road lingers. I’ve learned in public health classes that people tend to be bad at estimating risk. Anything that is involuntary, rare, or fear-based seems more risky, while things like car wrecks and heart disease seem almost normal. We can’t forget that status-quo has risks as well, and that people chronically underestimate the risks of the things they already do.Do not fail to undertake new adventures because they might be risky. What you are already doing might be risky. If you live a sedentary lifestyle and pick up biking, your overall risk of death decreases. The crazy-eyed SUV driver is out there and so are other objective hazards: parallel cracks in the sidewalk, railroad tracks, and the door zone. But you’re exercising and socializing and probably getting happier, putting you at less risk for obesity and cardiovascular disease and the other really big killers in the US.And why talk just about death. Maybe instead we can give a nod to the emerging field of hedonistic psychology and talk about happiness right here and now. Why not ride down the hill with the wind in your hair and go on long bike rides through the town and countryside and eat at diners and swim in rivers or go raid dumpsters at midnight and ride through the streets stuffing rolls in your mouth and howling at the moon. So what if cars have to go a little slower, and you have to keep your wits about you to avoid the right turners and cell phone talkers on your morning commute. At least you arrive awake, and full of energy, return home with the stress burned off. So I can’t wait to see where my parents go next. Especially if it’s on the road. jagged

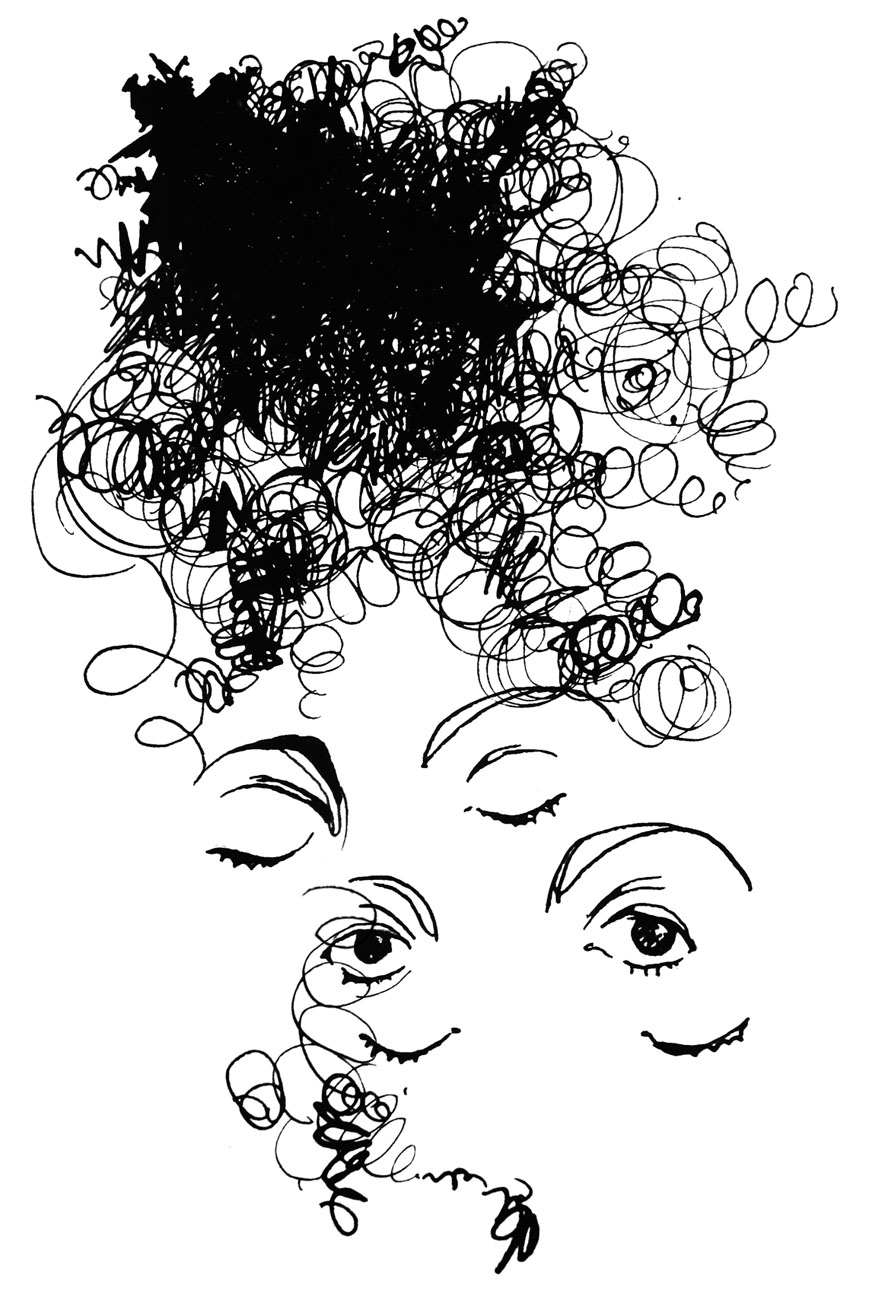

rain soaked

sky bursts

into

polychromatic fluorescent concentrate

blink

rain soaked curly spirals

curl and spiral along a line the jaw

line that tightens and releases

with rain soaked spiraling thinking thoughts

furrowed brows

reddened cheeks

pursed lips

tired eyes see me through caffeinated eyes

white bursts into blue and green I know

that much

blink awake

blink awake

again

it’s only being awake

blink awake

blink

while hard thoughts curl and spiral tear and tangle

all whorls and ruffles blinkblink mmmmm

outside thoughts awake

rain soaked

mud soaked wind

soaked run soaked

sun soaked

curl and spiral

into now

indigo

skies soft music

under parted cloud stars

The rains came hard.

For hours we stood, waiting

wet, hardly caring.

“It’s like a ballet. They move around in unison, and then there’s drama when the hawks come. It’s unique. It’s better than TV,” said Maren, my de facto tour guide to the vaux swift watch last Thursday night. We walked on the sidewalk approaching the Chapman School located in Northwest Portland, Oregon. Our necks craned upward as the concentration of tiny black birds intensified.

The destination for these birds was a brick smokestack, a relic of the early twentieth century school building. No longer used for its constructed purpose, the smokestack now serves as the nightly resting place of more than twelve thousand migrating swifts during the month of September. Every year since the early 1980s, the swifts have come to roost together in the brick column.

As I walked up the hill, a crowd of several hundred Portlanders emerged. Holding binoculars, sipping on root beer, and sitting on blankets, they watched as the birds formed a giant cyclone, spiraling into the chimney. “The birds are coming from the clouds in Portland and going in there!” one five-year old boy explained to me as he pointed to the chimney.

Several green-vested Portland Audubon members walked among the crowd to answer questions. Rob visited my group, explaining the lifestyle of a swift. He described how swifts never stop during the day. They can’t. Their feet are tiny garden rakes, stiff and incapable of grabbing branches. Their heart rate, only surpassed by hummingbirds, does not allow them to rest until night.

The dominate question involved the tornado of swifts taking part in their bedtime ritual. “They talk to each other and create this vortex. It’s a ritual they go through every night. The vortex is the most efficient way for them to get into the small hole,” Rob said.

Just then, a peregrine falcon erupted from the chimney empty handed. Screams and gasps from the crowd interrupted the casual evening conversations.

The vortex dissipated and formed a new cloud. Thousands of swifts chased the falcon. The new cloud became a serpent in the sky as it twisted and coiled to follow the predator. Some call it self-defense and others call it liberation theory. Either way, their plan did not work. The falcon, indifferent to the thousands of angry followers, looped around for another go.

“He got one!” yelled a spectator. His tone was a mixture of sadness and excitement. “You dirty bugger!” he continued.

As night fell and the final swifts found their place, the crowd grabbed their blankets and retrieved their bicycles. I walked back to mine, contemplating the significance of the evening. The night had a dizzying electricity to it. My psyche buried itself in undivided fascination as I tracked one bird after another.

Above all else, I loved how the swifts have found a place for themselves in the modern landscape. They could have found a hollowed out tree like their ancestors had been doing for thousands of years, but they chose a smokestack instead. The end result: the masses responded positively, welcoming change to their September evenings.

Is the choice of the swifts unrelated to the questions we face in our world today? The temptation is to lead a life of criticism, start over, and build a new community. But maybe such a retreat answers the wrong question. The question is not, how can we separate ourselves and make our world pure? The question is, can our worlds harmonize?

The unplugging movement represents more than the mainstream assimilation of modern environmentalism. The trend toward integrating green consciousness into the popular discourse is a step in the right direction. Yet, the notion that material culture can attain existential salvation by buying organics in re-usable bags leaves me unsatisfied, uninspired, and impatient. The consumption of feel-good-about-your-purchase labels packaged around marginally better goods and services only raises questions about the marketing campaign and a hollow feeling. After decades of hard-fought battles, we are toasting victory from a watered-down version of conservation, sustainability, and social justice.

Although good has come from the green movement, consumers still consume more than ever. Renewable energy, efficiency standards, and public policy hold promise for reducing the impact of our lifestyle, but one simple natural law trumps these well-intentioned efforts: if you create more, people will consume more. If more food is available, a species’ population will grow until it exceeds carrying capacity. When the population exceeds carrying capacity, it has to shrink until it reaches sustainable levels.

This logic applies to us as well. Our culture demands that we find a way to consume more. More resources, more energy, more consumerism is the surefire modern recipe for personal success and a growing economy. Technology may allow us to do more with less, but it doesn’t get at the heart of this problem.

We must simplify our material demands and take possession of our own identities. Reducing our dependence on the industrial life-support system for individual purpose, collective identity, and sustenance is the most reliable way to attain equilibrium with the planet and ourselves. Much more certain than waiting around for fusion-powered flying tractors harvesting local heirloom organics (although that would be cool).

Many material, economic, and socio-political obstacles stand in the way of mass simplification of our material lifestyles. What do I have to give up? Where would I live? What would I eat? Are there cars? What do I do for work? Is there even money? Are you suggesting we abandon it all and live like cavemen? These are worthwhile questions.

However, this isn’t where the rapid and spontaneous dismantlement of the current system (the Great Unplugging) begins; not with pondering the physical form of the future and doubts about measuring up to austerity. It starts with one question: “Is your soul prepared for drastic change?”

Win people’s souls and their minds will follow. Win people’s minds and their bodies will act accordingly. The best way to mobilize people to solve our present crisis is to get them excited about answering “Yes!”.

If success or failure of this planet and of human beings depended on how I am and what I do...How would I be?

What would I do?Buckminster Fuller

There is a tribe of nomads and travelers originating in the mountains of Western Mongolia and Central Siberia with pockets in the Pacific Northwest and as far as New Jersey and Alabama. These explorers travel light and carry little. Their largest bags are those filled with their stories, their memories, and their Love.

They are sustained by a dynamic balance of Communion and Autonomy, of Support and Freedom. To them it is as natural and necessary as breathing — coming together, letting go, coming together, letting go.

When two such nomads meet each other, after briefly pausing to honor the Mystery of Change, they hug emphatically. The ceremony is a reaffirmation of the paradigm that sustains their reality — coming together in Communion, then letting go in Freedom.

Riding across the Gobi desert towards the Center of Energy last summer, our small van packed with pilgrims popped a flat. While the driver put in the spare and we idly watched camels roam along the horizon, a young boy, who was studying to become a shaman, taught me the ritual.

We marked parallel lines in the dry earth, and stood opposite each other.

“This is the Panok-la, or Path of Now, symbolizing the gap between Perception and Awareness, from which Newness emerges. As we approach one another along the Path, be filled with the Wind of Mystery, and open to your yearning for Communion.

“When we reach One Place on the Path, we hug. Be That Hug — a whole greater than the self.

“As you let go,” the boy explained, “let Intelligence bow to the Divine Imagination, and set me free. At the same time, you set yourself free.”

Communion and Autonomy, as natural and necessary as breathing. But Time is not only a sustainable circle, it is also a line that accrues. The most insidious materialism is the karmic materialism, the materialism of doing.

“Do you own this Happening?” the rising full moon asks me, when the dew freezes and reflects the reflection, as I bivy alone in an alpine meadow in New Zealand.

The backpack full of stories and memories is always the heaviest. Who are you? Can you let it go? Can you die to your Self? Even the wisest nomads I’ve met struggle to lighten the load. Burdened, we suffocate. We fall together, then fall apart. Fall together, fall apart.

Only our Love Suitcase is weightless.A Video News Report from 2030....

Anchor: Touting their movement as a combination of the economic theories of Mahatma Gandhi and the political science of Buckminster Fuller, the Unplugged have now reduced the environmental impact of the United States of America by 8 percent over their 15-year program.

Opponents of the movement call Unplugging an unscientific and cult-like political movement, but proponents say that "Unplugging" was the best decision they ever made. Let's hear from Jack Houston, a former investment banker...

Cuts to video

[Screen opens to Jack Huston, a muscular early-40s New Yorker.]

Presenter: Jack, could you explain what Unplugging did for you?

Jack: Well, first we've got to cover briefly how Unplugging works. The core of the theory is that we can all live off the interest generated by our savings, or the profits from our investments, if we possess enough capital - and generations of Capitalists have dreamed of "getting off at the top" - making enough money to cash out of the workplace and live as they like for the rest of their lives.

Presenter: But what does that have to do with living in a housing pod in the middle of Oregon?

Jack: Well, it comes down to the nature of capital. Wealth stored as dollars was essentially a share in America's national economy - a credit note backed by the US Government. But Buckminster Fuller showed us that wealth-as-money was a specialized subset of Wealth - the ability to sustain life.

To "get off at the top" requires millions and millions of dollars of stored wealth. Exactly how much depends on your lifestyle and rate of return, but it's a lot of money, and it's volatile depending on economic conditions. A crash can wipe out your capital base and leave you helpless, because all you had was shares in a machine.

So we Unpluggers found a new way to unplug: an independent life-support infrastructure and financial architecture - a society within society - which allowed anybody who wanted to "buy out" to "buy out at the bottom" rather than "buying out at the top."

If you are willing to live as an Unplugger does, your cost to buy out is only around three months of wages for a factory worker, the price of a used car. You never need to "work" again--that is, for money which you spend to meet your basic needs. However, there are plenty of life support activities to keep you busy, and a lot of basic research and science to do. Unplugging is not an off-the-shelf solution, it's a research career!

Presenter: So tell us about your house over here? It looks pretty weird!

Jack: Unpluggers don't have our own manufacturing facilities for these yet, so we shop them out to fabs in Turkey. The shell is aluminum and aerogel, 50 percent collector panels, 12 volt appliance wiring, super-insulated windows with liquid crystal shades for internal temperature control. Heat comes from either a wood stove or a peltier solid state heat pump running off ground heat, depending on how much power we need. Cooling, similarly. We cook in the solar oven on the side sometimes, but mainly on woodgas or in the microwave.

The houses - or "Pods" as you call them - have a reputation as being "one size fits all poorly" but, in fact we found that 90 percent of people got on very well with one of three basic designs. The economies of scale made mass manufacture of those models more cost effective but people still do custom work for about one unit in ten.

We're working towards local fabs for a lot of this stuff now, but that's hard to organize without winding up with internal industries which run on grid power and commercial supply chains, both of which are no-nos for our way of life: you can't be an alternative if you still rely on the industrial infrastructure for your basic daily lifestyle needs. So we build the housing pods in Turkey as part of the "Final Purchase" process - where a person becoming an unplugger buys their home, tools and land, to support them and their family for the rest of their life, and then disconnects from the national economy.

It's not perfect. We're still using the resources of the industrial world to disconnect from it. But until we have green fabs for the collector panels and other necessities, it's what we have to do.

Presenter: Can you explain what this has to do with Fuller and Gandhi?

Jack: Gandhi's model of "self-sufficiency" is the goal: the freedom that comes from owning your own life support system outright is immense. It allows us to disconnect from the national economy as a way of solving the problems of our planet one human at a time. But Gandhi's goals don't scale past the lifestyle of a peasant farmer and many westerners view that way of life as unsustainable for them personally: I was not going to sell my New York condo and move to Oregon to live in a hut, you know?

Presenter: Ok.... with you so far.... what about Fuller?

Jack: Gandhi's Goals, Fuller's Methods, if you like.

Fuller's "do more with less" was a method we could use to attain self-sufficiency with a much lower capital cost than "buy out at the top." An integrated, whole-systems-thinking approach to a sustainable lifestyle - the houses, the gardening tools, the monitoring systems - all of that stuff was designed using inspiration from Fuller and later thinkers inspired by efficiency. The slack - the waste - in our old ways of life were consuming 90 percent of our productive labor to maintain.

A thousand dollar a month combined fuel bill is your life energy going down the drain because the place you live sucks your life way in waste heat, which is waste money, which is waste time. Your car, your house, the portion of your taxes which the Government spends on fuel, on electricity, on waste heat... all of the time you spent to earn that money is wasted to the degree those systems are inefficient systems, behind best practices!

Presenter: Wow! So tell us about the Humane Human Footprint.

Jack: The Human Footprint is simple: it's the share of the world's resources you can use without really harming anybody simply by existing. We call it the Human Footprint as opposed to the Inhuman Footprint. You take the sustainable harvest of the earth - the bounty we can consume without reducing next year's harvest or reducing the resilience of the earth in other ways - and your share of that is one Human Footprint. The earth's Wealth - its life-giving power - is like a trust fund split between seven billion humans and a gazillion other living creatures. That which consumes more than its share is defrauding all the rest of their right to life. And this isn't religion, this is common sense: if there are winners and losers, we're in a race for survival. If there are only winners, we're all artists, scientists, lovers and scholars.

I know how I want to live.

Presenter: So how close to your Human Footprint are you, Jack?

[Jack looks uncomfortable.]

Presenter: I've heard five times over is a typical number for Unpluggers...

Jack: Well, it depends how you measure it but yes, about that. I have three children, so my family footprint is about 11.2x HF but my personal footprint is about 7.3x. I'm working on it, though. It's hard to make the adjustment, and we only have a few tens of thousands of people at 1.0x or lower.

Presenter: So let's talk politics. Unplugging is also a political movement - you yourself are mayor of a township here, and your "town" is the local Unplugger population plus a few hold outs in ghost suburbs east of here. Why play at politics if all you wanted to do was drop off the Grid?

Jack: Because political assumptions wire everything. Building codes dictate how you can build, which dictates the size of your housing cost, which is the primary factor in your Unplug Cost. Our sanitary systems are greatly more effective than those of the Grid but, because we fertilize food with human waste after extracting what energy we can from it, some say our food isn't suitable for human consumption - even though, in fact, there is no scientific evidence what-so-ever of any disease organisms in the fertilizer stream. Just the idea of fertilizing using processed human waste freaks people out, even though it is how humans always lived. And this pattern repeats for water, our medical practices, all of it. You would think that preventative medicine was a crime!

Because we are different, the existing legal infrastructure works against us at every hand and turn. To create change, we have to play politics. But we are careful to simply use our small-but-growing clout to open doors for our chosen lifestyle, not to close doors on other people's choices. We aren't ecostalinists. Gandhi's approach: voluntary enlistment in the army of truth, if you want to think about it that way, has proven to be the only effective model of political change which is consistent with all of our shared values. We embrace some parts of Gandhi's model more than others - as with Bucky - but you can't argue with the historical success of his approach: India, South Africa, America, Poland, Mexico... the list goes on.

Presenter: Even my kids have an Obey Emperor Gandhi bumper sticker. What's that about?

Jack: It's an Unplugger joke. We call Gandhi "Emperor Gandhi" because in our way of looking at things, he was the political leader of India - a network of Kingdoms - and therefore technically he was an Emperor [laughs]. In that role, he organized collective defense against the invasion of India by raising a volunteer army of people who bought nothing from the invading colonials, made salt, and got beaten while maintaining rigid discipline - just like an army. All they did not do was leave home or use violent methods to resist their invaders. The fact Gandhi himself didn't own much of anything and advised self-reliance as a keystone of freedom makes him the John Locke of our movement. But we don't take the Emperor Gandhi thing seriously, you know. It's just a bit of our cultural humor.

Presenter: The threat of "Mom, keep yelling at me and I'll get a job delivering chinese food and then Unplug when I've saved up!" has kept many a parent up at night...

Jack: Unplugging isn't really something you can sustain from youthful rebellion: kids who don't choose this way of life for themselves as adults are usually really poor Unpluggers - they don't take soil metrics seriously, they don't really understand the invest-in-your-lands model of labor, and so on. It's not really something for punks and anarchists, even though there is superficial appeal.

Presenter: There's a lot of science here!

Jack: Oh yes. We monitor everything we have proved pays, and more: soil bacteria genetics, nutrient levels in the soil, nematode populations, you name it. We have such excellent yields and pest control because we don't move around much - we get to know our land as scientists and artists and designers - we share knowledge and models.

Of course, not everybody contributes equally to this knowledge base - I have a neighbor who is a molecular biology professor by (former-) trade and, well, I use his numbers a lot [grins]. But we all do what we can, and the results are proof that our farming techniques - "high monitoring biointensive agriculture" or "Technical Permaculture" depending on where you live and which school you follow - our farming methods work, and will continue to work for at least a few hundred to a few tens of thousands of years.

And that's enough for us: leave it to our children to figure out how to get their own lives to be even more integrated morally, ethically and socially.

Presenter: Some say that Unplugging is a cult because of your "Unplugger Morals" doctrines...

Jack: Acting as if the god in all life mattered is radical politics. But we have people from every faith and tradition living as Unpluggers, as well as those with no beliefs but a deep moral conviction that this is the right thing to do. But as with Satyagraha - Gandhi's social change approach - this takes everything you have and more and you can't do it without a solid internal framework, a deeply personal commitment to this as Right Action in a Buddhist sense, as Dharma from a Hindu perspective, as The Life Divine if you are a Christian. We have radical Benedictine monks - on the edge of getting booted out of the Catholic Church - who have updated the lifestyle passed down from Benedict himself to use Unplugger Farming and who became part of the Unplugger Community as a result. But we also have anarchosyndicalist atheists.

All it takes is a belief you can act on which helps you make personal changes for global reasons. And a political faith isn't usually enough to do that, but it can be. Religion has proven over time that it can move people in ways that nothing else can, and Unplugging is the biggest change a society can make.

Living up to your values is hard. Faith helps some people do it, so we tend to see more of those kinds of people making the switch. It's just a selection bias.

Presenter: What do you mean "a change that society can make?"

Jack: Unpluggers now constitute 5 percent of the United States population. At first, we were the very ideologically motivated, and there was a lot of interface with older communitarian groups and prior generations who had attempted to make this transition.

But as we became more defined, and our thinkers elucidated our case more clearly - as our farmer-scientists began to really get the yields predicted in theory, on a per-square-foot basis... it became clear that we were talking about a partial solution to the problems that have faced the human race from the beginning of time: how do I live myself, and how does my family live.

And a society is just individuals and families, and sometimes families of families, all the way up to States and Governments and the International Agencies and so on. If you solve the problem for a single family, and it's something which can compete in the evolutionary marketplace of ideas, then eventually you can solve the entire problem.

You know why GDP has gone down 20 percent because of Unplugging? Unpluggers are entrepreneurs. We used to start businesses because we wanted to buy out at the top of the game, now we usually buy a fairly lavish Pod, and some really, really good quality land, unplug by 30, and some of us expect to spend the rest of our lives learning, teaching and exploring what it is to be alive. Farming five or six hours a day seems like a lot of work, but you do it with friends, and you're doing science and research some of the time, and you eat what you make. The basic activities of life are so much more satisfying that earn-and-spend-and-eat-carry-out when you actually respect them as basic human activities, as links we share with everything that is alive.

Presenter: Tell me about the Endowment.

Jack: The Endowment is how we help the poor to Unplug, and it is easily the most controversial part of our program. We encourage the developing world to Unplug as the ultimate form of Leapfrogging: skip hypercapitalism and anarchocapitalism and democratic socialism entirely and jump directly to Unplugging. Many Unpluggers take their excess capital, keep investing it in the system, and use the proceeds to fund private Unplugging programs. Others simply took their capital and added it to funds managed by a Grameen-bank like institution called the Unplugging Bank which lends people money to unplug, and has them pay for their Pods by selling excess farm goods and teaching agriculture for us. The leverage of these approaches has yet to be verified but - judging by the political repression of Unpluggers in China and India and some parts of Africa - judging by that resistance, I think we are going to be successful.

As the Mahatma said: "First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win."

Software used to be an industry, you know?

Presenter: Thank you, Jack, for telling us about your life.

I am the man who walks up escalators!

Or if given the option of stairs

bounds up them with even less care,

Simply to compete

with those who stand at ease

upon their ascending machine.

No! I do not care if I win!

Do you take me to be that vain?

It is the very pump of my muscles

that drives my legs!

The joy of use

that marks my move!

What do I stand to lose?

When I give up my youth

and stand upon their lethargic chariot

Spent, tired, and tragic.

I see no future, I feel no doubt

No opaque overwhelming cloud.

I hear only laughter in the call

of swift and pounding footfall.

Early this fall I unplugged for three weeks. Turned off my phone, took a Facebook sabbatical, squashed my compulsion to check email, and bade my friends farewell while I hiked, danced, climbed, ambled, dined, spectated, and contemplated on my own terms across three states and one province.

In the corporate America where I typically spend 40-plus hours of my waking life each week, arranging such a long respite is considered a feat. A sampling of responses among the people I told of my plans: “Who approved that?!” “Wow, I wish I was your age again!” “That’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Good for you!”

Personally, I’m under no delusion that a few weeks of North American travel is akin to retreating to the far-flung exoticism of Lombok or the purifying intensity of an ashram stay in a remote corner of India. Hardly.

As something I craved in order to collect, reconfigure and orient myself in the midst of what has been a tumultuous year, the three-week break succeeded enormously. Paradigm-shifting? No. Simply constructive? Yes. That’s all.

But the real story goes back to those reactions.

That taking a few weeks off to reconfigure elicited such wonder is itself a wondrous thing. Is society really so enslaved to the idea of career, routine, family, friends, and money that any attempt to distance oneself from that — even for a paltry three weeks — is now met with sheer awe by other people?

In their reactions I sensed an attitude of: “Well, good for you. I wish I could do that but I need to stay put and focus on my job-family-mortgage-school-dog-favorite TV series.”

These days, to unplug, whether for just a few weeks or indefinitely, is to put the American Dream on hold. It is a sign of listlessness or self-doubt. It is a luxury reserved for a few, mostly the young, seeking a forum for legitimizing their aimlessness. It is either for the yuppie, the trustafarian, or the trendy idealist.

How unfortunate that a humble desire to shift one’s stance or adopt a new perspective through rejecting, or just briefly pausing, society’s live-to-work mentality is seen as unattainable or viewed skeptically by others. It should be integral to the American Dream (the idea that each of us can harness our unique, unlimited potential to achieve success), not antithetical to it.

The practice of discernment, of retreat, of carving out the space to build and practice an intentional life has turned into a foreign concept.

I’m belaboring this idea because it’s the aspect of unplugging that I’m most concerned with. At once I am both a working professional, deeply engaged in the day-to-day affairs of my career, friends, family, hobbies, and the like; and I am also a culturally critical person fighting an uphill battle to create an intentional, creative, spectacular life amidst a consumption-driven society.

I suspect you, dear reader, share this mindset and this challenge. So what to do?

As much as I’d love to uproot and move indefinitely to a Danish commune, set up a produce stand in Northern California, or bounce from village to village in Guatemala, that kind of unplugging is not realistic for me or most people. Capitalism’s hold on us is too great. At some point a bill will arrive and the experience will fall apart.

Marx’s idea of historical materialism correctly accounts for the economy’s function as the basis for all aspects of society. Sad but true. We cannot escape that. Short of discovering a suitcase of money or scoring an outsize parental subsidy, our reality is at its essence based on the fulfillment our basic economic needs (such as food and shelter). This materialism is the root of our social existence, which in turn determines our consciousness, says Marx.

Debbie Downer would point out, and I would agree, that sooner or later, the commune will fall prey to unpaid taxes, the produce stand will be made irrelevant by the arrival of a nearby grocery store, and the savings used to fund that Guatemala village hopping will run dry.

Then what? Game over; back to the rat race — probably in a weaker position than before you left. Of course, most people never leave to do something like this in the first place out of, largely, financial fear. At the end of the day, people in most places of the world are hemmed in and governed by the market’s invisible, dispassionate, powerful hand. My pessimism on this subject prevents me from taking that quixotic leap to Guatemala.

But I actually don’t think such drastic leaps are necessary in the first place.

We all possess, right now within ourselves, the constitution and tools required to achieve contentment. Leaping from one location or vocation to another doesn’t change that fact — and may actually obscure it, prolonging that end which we seek.

Simple, unplugged, intentional living is attainable through small gestures that are compatible with the contemporary urban lifestyle. And it should not be seen as an out-of-grasp luxury reserved for the new age granola crowd with too much time on its hands.

A week or two of travel. A do-it-yourself philosophy. Bicycling. Taking a new class. Letter writing. Shopping local. Aimless walking. A weekend-long email break.

These are all easy, achievable ways to detach from business as usual, refresh oneself, or subvert dominant paradigms. Doing these things should not elicit awe among your personal network of people; rather, they should be seen as commonsense and ordinary as brushing your teeth. Surely a stagnant life is as bad as a cavity, right? Well, you certainly wouldn’t think so based on how little attention people devote to self-assessment and carving out the space required for it.

If we are to do the essential work of discovering our own true selves and creating a meaningful existence, then we must unplug. Vanish. Retreat. Upend our conventions.

This should happen in two ways.

First, literally unplug. Technology’s firm grip on us has unleashed enormous gains in productivity and knowledge over the past 20 years, but its ugly side–a crushing overload of information–has become increasingly apparent.

Attending to the constant stream of texts, phone calls, emails, news articles, videos, music, tweets, and status updates that is pushed in front of us each day is a nearly impossible task. Suddenly, we spend each day in a reactive mode, sorting through what’s been presented to us, rather than in the creative, proactive mode necessary to empower serious discovery and invention.

Second, once those incessant content streams are gone, we can come to understand and deal with our materialism. By identifying and deconstructing our attachments — to money, career, cars, food, status, power and even friends and family — we start to unleash our authentic creative being. This process is absolutely essential for cultivating contentment, self-sufficiency, and confidence.

In breaking through materialism we are up against a powerful force. “The deepest craving of human nature is the need to be appreciated,” said William James. Materialism tends to be our go-to attempt at nurturing that craving, and it usually succeeds wildly. We grow accustomed to our income, house, ego, social life, etc. and find it hard (or, after a while, unnecessary) to let go or seriously question them, for fear of what lies beyond that transcendence.

But question them we must, for, as the urban shaman Gabrielle Roth notes, “… the security of dependence is actually the insecurity of not controlling your own life, or being your own person.” It is my belief that through small, occasional acts of unplugging we can begin to see the truth in this idea and finally summon the courage to confront our own materialism to control our own life.

I had three weeks to do this, others can spend three years, and others might have 30 minutes. The duration isn’t especially important; the will to unplug is. At the very least, simply pausing once each day to question a routine behavior or think intentionally begins to build a self-awareness that chips away at materialism, increasing one’s autonomy and creative power.

This discussion cannot end without acknowledging the American transcendentalism espoused most famously by Emerson and Thoreau.

Speaking at Harvard in 1837, Emerson prodded the students to make a clean break with European tradition and custom in order to forge ahead in defining America’s distinct, unique character. Instead of taking the well-worn path, he urged the students to take on the cross of self-discovery and independence in spite of the “nettles and tangling vines” that get in the way of self-directed people.

What is the benefit of doing this, despite the strain of invoking societal skepticism? Because that person, he said, “… is to find consolation in exercising the highest functions of human nature. He is one, who raises himself from private considerations, and breathes and lives on public and illustrious thoughts. He is the world’s eye. He is the world’s heart. He is to resist the vulgar prosperity that retrogrades ever to barbarism, by preserving and communicating heroic sentiments, noble biographies, melodious verse, and the conclusions of history.”

Later, he continues, “In yourself is the law of all nature… in yourself slumbers the whole of Reason; it is for you to know all, it is for you to dare all.” Explore–begin to call out into yourself, and let the echo seduce you further in.

The most famous instance of the unplugged, off-the-grid life is Thoreau’s Walden Pond experience. His observations reveal that our contemporary concerns existed in his time as well:

“Most men, even in this comparatively free country, through mere ignorance and mistake, are so occupied with the factitious cares and superfluously coarse labors of life that its finer fruits cannot be plucked by them. Their fingers, from excessive toil, are too clumsy and tremble too much for that. He has no time to be anything but a machine.”

More than one hundred and fifty years later, resisting the machine continues to form the basis of our post-modern existential conflict. We can learn much from Thoreau’s experience and apply it today.

However, although Thoreau’s experience was certainly transformative and yielded the incredible insights that form a classic book, we have to remember that his retreat was not really that drastic an undertaking. He lived in his cabin for just two years, the whole time located only two miles from the nearest town. He had regular visitors.

Let go of your image of having to quit your job, sell all your belongings and move to a shack in Africa in order to realize a spiritual reawakening or break from normalcy. If someone has the time and money to do this, excellent. I envy that person and suspect that great truths will be realized in such an endeavor. But for those of us for whom something so grand and severe is not a viable option, we can have similarly transformative experiences on a smaller scale.

Seek out, take advantage of, and protect whatever little moments and experiences you can to build space in your life for reflection and thoughtful action. They are essential, not optional or unattainable, for our self development.

Doing this is possible; it is manageable. And it is within reach for us all right now.